THE STORY OF ZAYNIDDIN BABA

In the seventeenth century, Tashkent was organized into four administrative districts (daha), each of them associated with a patron saint. Qaffal Shashi (Shafeʾi faqih, d. 976) was the patron of Sibzar district, Zangi Ata (Yassawi sufi, d. appr. 1258) was the patron of Bishagach, Shaykh Khawand Tahur (Yassawi sufi, d. 1355 or 1359) was the patron of Shaykhantahur and Shaykh Zayniddin was the patron of Kukcha. Among them, only Shaykh Zayniddin was a nonlocal saint for Tashkent. However, the importance of Shaykh Zayniddin’s shrine in the spiritual life of the city increased again and again. The mausoleum of Shaykh Zayniddin has become one of the main religious buildings of the city. How did this foreign-born Sufi master become one of the most popular saints of Central Asia?

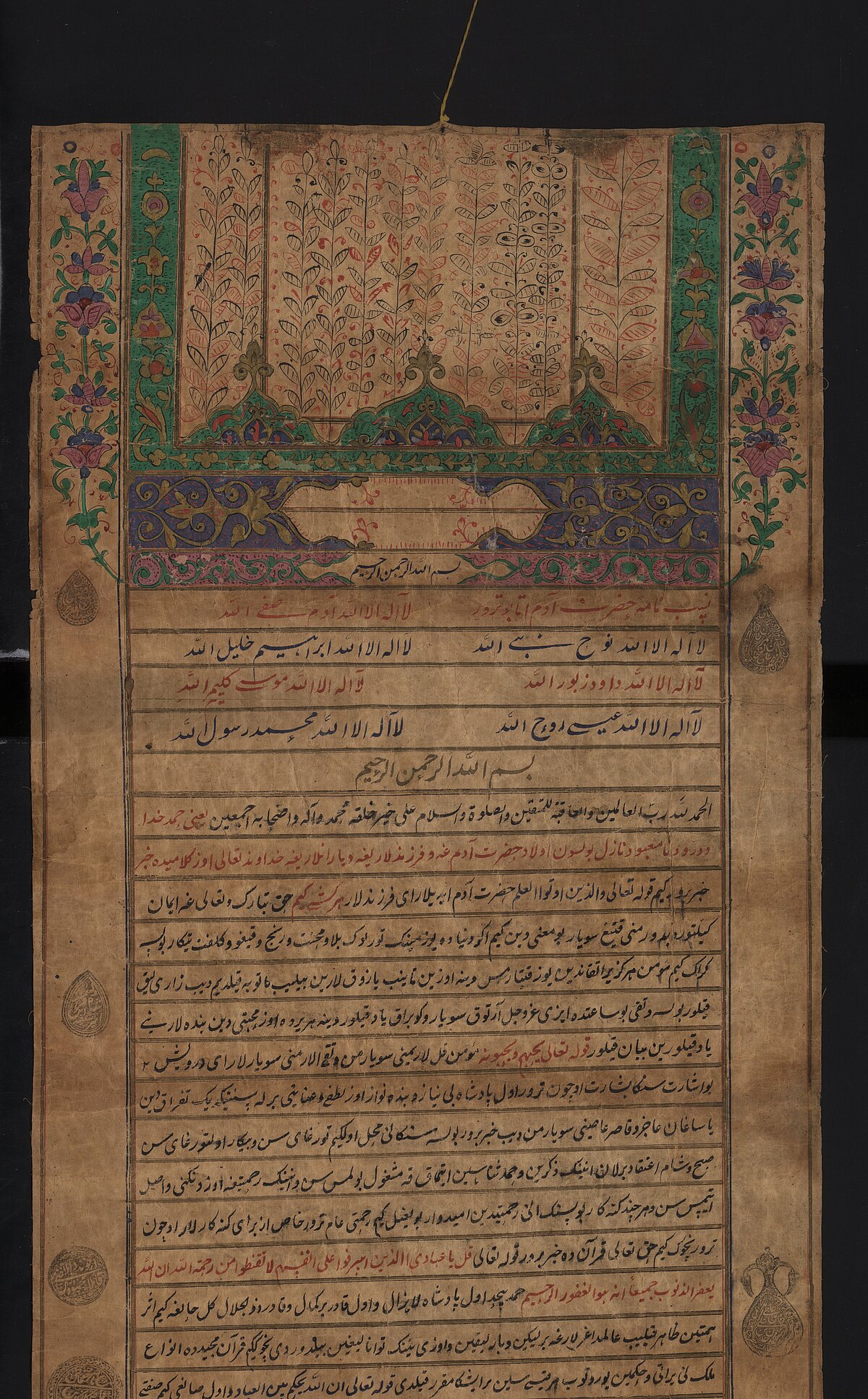

Shaykh Zayniddin Kuy-i ʿArifani, known as Zayniddin baba, lived during the 12th and 13thcenturies in the village of Kuy-i ʿArifan outside of Tashkent, for which the title Kuy-i ʿArifani was given to him. Another view is that he was honored as Kuy-i ʿArifan (the street of knowing) or Kuh-i ʿArifan (the mountain of knowing) because of the respect he possessed among Sufis. However, no extant local hagiography is specifically dedicated to him. Only a little information about him can be found in hagiographies and genealogies from the 16th century. These sources confirm that Shaykh Zayniddin was the son of Shihabiddin Suhrawardi (1145–1234) and came to Tashkent from Baghdad. Interestingly, Shamsuddin Dhahabi (1274–1348), Suhrawardi’s biographer, only mentioned one son, Imamiddin Muhammad (d. 1257), who took his father’s place after the latter’s death. (Dhahabī, 788). But the Central Asian and Indian hagiographies say that Suhrawardi had two more sons. One of them was Shaykh Zayniddin who was buried in Tashkent, and the other Shamsiddin Muhammad Turk Biyabani (d. 1240), buried in Delhi.

The description of Shaykh Zayniddin’s arrival in Mawaraʾunnahr can be seen in the “Manaqib-i Nuriddin Basir” of Abulhasan (ca 14th c.) and “Lamahat min nafahat al-uns” of ʿAlim-shaykh ʿAzizan (1564–1632). Abulhasan narrated that Shaykh Zayniddin, who was his ancestor’s spiritual guide (pir), visited with Khwajah Ahmad Yassawi for a conversation. The second author, ʿAlim-shaykh ʿAzizan was the 11th descendant of Shaykh Zayniddin and relied on Abulhasan’s “Manaqib-i Nuriddin Basir” in narrating the same story. Additionally, he described an event that happened before the meeting of the two Sufis. According to him, Shaykh Zayniddin decided to visit Turkestan with Mustafa ʿArif, who was a descendant of Junayd Baghdadi (830-910) and Suhrawardi’s servitor (khadim) (Ṣiddīqī-ʿAlawī, 335).

It is not surprising that Shaykh Zayniddin went to Tashkent from Baghdad to promote Sufism after the Mongol invasion. The question is what Sufi order he took. If we consider Shaykh Zayniddin’s origins, it is natural that he would have belonged to the Suhrawardiya order. Some sources, however, introduce Shaykh Zayniddin as a representative of the Khwajagan or Uwaysi order. Whatever the case, it is clear that he had many disciples. The most famous among them was Shaykh Nuriddin Basir. In the “Manaqib-i Nuriddin Basir,” Abulhasan described Nuriddin Basir's relations with his spiritual guide. Additionally, there are notes that Shaykh Zayniddin wrote rubaʿi verses in Persian, like other mystics of the time. For example, this rubaʿi is attributed to his pen:

گفتم رخ خود بگونۀ کاخ مکن

کس را ز من و کار من آگاه مکن

گفتا که اگر رضای ما میطلبی

چون میکشمت دم مزن آه مکن

(Abulhasan, f.57a)

I said, don’t turn your face into some fortress,

don’t tell anyone about me or what I do.

I said, if you want to make us happy,

Don’t talk, don’t sigh while I’m killing you.[1]

Modern authors claim that the current mausoleum of Shaykh Zayniddin, located in the old city of Tashkent, was constructed by Amir Timur (d. 1405). However, it was common in the region to attribute mausolea to Timur or other famous rulers to increase their significance and the legal force of their founding documents. It is more plausible that the main mausoleum was built by the Shibanid rulers Baraq-Khan (r. 1533–51) and his son, Darwish-Khan (r. 1551–79), who carried out many construction projects throughout Tashkent. The appearance of the endowed (waqf) properties of the grave, as well as the legalization of the official genealogies of the saint's descendants, occurred precisely at this time, as well. Also at this time, a new line of Central Asian Siddiqi khwajas Kuyi-arifani was formed. In the 17th-19th centuries, khwajas of the Kuyi-arifani lineage managed the waqf properties and occupied religious positions in the city. During this period new branches of the family were formed in Samarkand and Bukhara. Among them, the Yassawi shaykhs Darwishaykh (d. 1551), ʿAlim-shaykh (the author of “Lamahat”, d. 1632), and Amir Bahauddin (killed 1681) became famous in the Sufi environment and political life of Bukhara khanate of the 16th-17th centuries (DeWeese, 398).

The tomb in Tashkent was reconstructed many times. The main structure is quadrangular (16x18 m) with a height of 20.7 m, and many portals on each side of the building. In the center of the mausoleum sits a large grave marker belonging to Shaykh Zayniddin. Surrounding it are other graves, according to the oral history belonging to his wife and children.

Next to the tomb, there is a small strange underground structure. There are legends among the population that this was the Sufi meditation cell (chilla-khana) of Shaykh Zayniddin himself. They say that under the cell was an underground passage leading straight to the mausoleum of Qaffal Shashi, four to five kilometers away.

In the early 1990s, during the renovation of the mausoleum, it was discovered that the cell was designed as a primitive observatory for observing astronomical phenomena. There are special openings in the lower and upper domes of the cell. From the lower room of the cell once a year one can observe the sun during the day and other celestial objects at night. The niches in the walls of this room show the direction of the eight points of the compass. According to astronomers, this cell is the only structure of its kind in the world equipped as an observatory. The room had a function similar to that of a calendar. Later, the chilla-khana of Shaykh Zayniddin’s sanctuary was built above the ruins of this observatory (Tursunov & Azizov).

How did the mausoleum of Shaykh Zayniddin become a place of pilgrimage? The author of “Mulkhakat bi-s-surah” Jamal Qarshi, who came to Tashkent in 1272 and 1290, did not mention either Shaykh Zayniddin or his grave. But by the end of the 13th century, the grave had become a famous sacral place. For example, Shaykh ʿUmar Bagistani (d. 1291) visited the grave of Shaykh Zayniddin twice. The first time he came asking for a child. After his son was born, he visited again searching for a name for his son, which he heard in the sound of doves at the mausoleum. His son, Shaykh Khawand Tahur, became another of Tashkent’s patron saints. This became the most famous story about Shaykh Zayniddin and further strengthened his reputation as a saint not only among the Sufis but also among the local population, since ʿUmar Bagistani and Khawand Tahur are two of the most famous Sufi figures in Central Asia.Bagistani’s pilgrimage may be related to his affiliation with the Suhrawardiya sect. However, in the 15th and 16th centuries, famous Naqshbandi Sufis Nizamiddin Khamush, Khwaja Ahrar, Mawlana Qazi, and Makhdumi ʿAzam also visited Zaynuddin’s tomb.

There are many reasons why the popularity of this saint of obscure origins had grown so much as to become one of the patron saints of the city. The narration on the pilgrimage of the childless Shaykh ʿUmar Bagistani to Shaykh Zayniddin's shrine and the naming of his son Shaykh Khawand Tahur in this place, brought the personality of Shaykh Zayniddin wide popularity both in later Sufi hagiographies and among the population. During the reign of the Suyunchid clan of Shibanids (1512-82), several new sacred buildings were built in Tashkent, including the mausoleum of Shaykh Zayniddin. At the same time, his descendants legalized their genealogies in the documentary record (with a nasabnama and royal deeds) and ideological texts (Lamahat). The mausoleum of Shaykh Zayniddin was the sacral center of his descendants or Kuyi-ʿArifani line of Siddiqi khwajas, who were Sufis and religious officers. After the people of the Kukcha district chose Shaykh Zayniddin as their patron, his mausoleum became one of the main pilgrimage sites in Tashkent. One of the last mass cult city ceremonies took place in 1872, when cholera spread in Tashkent and the head of the ʿulama,along with local administrative officials, agreed to sacrifice a camel in this shrine, indicating its significance at that time.

Shaykh Zayniddin’s influence in history is not limited to Tashkent. Muhammad ʿAbid, son of ʿAlim-shaykh (killed in 1687, in Golconda), entered the service of Aurangzeb (r. 1658–1707). His son, Mir Shihabiddin (d. 1721), summoned from Bukhara, and cousin Mir Muhammad Amin (d. 1721) were leaders of the Turani group, exerting their influence on the political life of the Baburids (Athar Ali, 18). Mir Qamariddin b. Mir Shihabiddin (r. 1724–48) as Nizamulmulk I Asafjah founded the Asafjahi dynasty (1724–1949) in the Deccan. This is the beginning of a new story about Shaykh Zayniddin’s descendants in the Indian subcontinent.

[1] This verse is also found in the diwan of Abu Saʿid Abu’l-Khayr, with a first line that reads, “Don’t turn my face straw-colored” (i.e., sick with love): Saʿīd Nafīsī (ed.), Sokhanān-i Manẓūm Abū Saʿīd Abū’l-Khayr (Tehran: Nasāʾī, 1955), vol. 3, p. 76 (number 521). Thanks to Sara Mirahmadi for making this connection.

References

Abulhasan. Maqamati Shaykh Nuriddin Basir. Al-Biruni Institute of Oriental Studies. Ms.3061/2.

Athar Ali. The Mughal Nobility under Aurangzib. Bombay, 1966.

DeWeese D. The Yasavī Order and Persian Hagiography in Seventeenth-Century Central Asia. ‘Ālim Shaykh of ‘Alīyābād and his Lamahāt min nafaḥāt al-quds / Studies on Sufism in Central Asia. IX. 2012. P.329-414.

Dhahabī, Shamsud-din Muhammad ibn Ahmad. Tārīkh al-islām wa wafayāt al-mašāhīr wal- a‘lām. Vol. XIV. 631-660 H. Beyrouth, 1424/2003.

Ṣiddīqī-ʿAlawī, Shaykh Muḥammad ʿĀlim. Lamaḥāt min Nafaḥāt al-quds. Islamabad-Lohur, 1986.

Tursunov, O.S., and S.H. Azizov, "A Medieval Observational Instrument in Tashkent," Journal for the History of Astronomy 33.1 (2002): 41-44.