MATERIAL TALES FROM THE LAND BEHIND BUKHARA

Over the past years, the Institute of Iranian Studies has closely collaborated with the Mission Archéologique Franco-Ouzbèke dans l'Oasis de Boukhara (MAFOUB), which runs a project of excavations in the Bukhara Oasis (left). The oasis is conventionally considered part of Sogdia, understood as the territory between the rivers Syr- and Amu Darya in present day Uzbekistan.

Our engagements and contributions regarding the ongoing research in the oasis include a fresh approach to the historical narratives of political and social developments (Schwarz 2022) as well as the reconstruction of a material history of Bukhara’s population based on the systematic and integrated study of the ceramic material (Puschnigg and Bruno [2024]). In contrast to previous approaches to pottery analyses in the oasis that primarily valued its potential as dating evidence and sought to define fixed consecutive stages in its development, we aim to explore comprehensively changes and advances in the ceramic industry, the development of local markets as well as patterns of consumption as a continuous process in the long durée. Last season’s finds from the urban site of Ramitan (above) promise to be of particular significance in these regards. We will introduce some of the most prominent pieces below and contextualize them within our present research.

The archaeological field work undertaken by the MAFOUB revealed that the settled history of the Bukhara oasis only began with the end of the 4th or beginning of the 3rd centuries BCE (Rante and Mirzaakhmedov 2019). At the time, the historical-political neighbours of Bukhara included Khorezm (the region around the delta of the Amu Darya), Chach (Tashkent oasis), Sogd proper (the middle Zerafshan around Samarkand), the Qasqadarya oasis, Bactria (south-eastern Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and northern Afghanistan) as well as Margiana (Merv oasis, Turkmenistan) south of the Amu Darya (Oxus). Only in the late antique period and specifically from the time of Bukhara’s Islamisation during the 8th and 9th centuries CE a stronger political integration is traceable in the sources and archaeological evidence that leads to a centralised administrative system of the Bukhara oasis, which now appears as a political unit (Rante, Schwarz, and Tronca 2022, 145–46).

MAFOUB excavations explore and document the archaeological stratigraphy at each site context by context. During excavations charcoal samples are collected, where possible, for radio-carbon dating to obtain a sequence of reference points for the site’s absolute chronology. Regarding material culture, ceramics make up by far the largest part of the finds. A single archaeological context may contain scattered fragments of different ceramic vessels that originally belonged to distinct chronological periods. This is, for instance, the case with construction waste, which results from the demolition of older structures and which was often used to raise floor levels or fill in rooms in preparation for new building developments. Correspondingly, one of our objectives is to carefully examine the pottery assemblages from each context with regard to its composition, the state of material preservation, traces of wear and/or use and re-use, respectively. In this way, we can distinguish between vessels that are roughly contemporary with the archaeological context and its absolute date and those fragments that are likely residual and belong to an older phase, gradually building a refined relative chronology for the pottery.

Our analyses to date demonstrated, that despite the numerous stratigraphic excavations, some phases in the settlement history of the oasis are much better reflected in the material than others. This relates to the dynamics of development or urbanization at each site leading to different parts of a city or village showing distinct sequences of occupation and abandonment (Rante and Mirzaakhmedov 2019). Another factor is that individual occupational phases were destroyed through subsequent building activities and consequently do not leave many traces in the stratigraphic sequence.

In the last two seasons, fresh excavations at the small town of Ramitan (Uzbek Romitan) (left) have revealed significant material assemblages that shed light on the late antique 3rd - 4th centuries CE and later pre-Islamic phases between the 6th and 7th centuries CE, a period that so far has been underrepresented in our material. The recent excavations targeted areas adjacent to the palace structure (Ramitan M, 39°54'37.36"N 64°16'10.67"E) and outside the citadel in the lower city (Ramitan N, 39°54'33.51"N 64°16'6.28"E). Ramitan M revealed the structure of a fortified building, which was excavated almost in its entirety. This excavation area was only truncated in its outmost western part through an old 20th century archaeological trench. Work in the lower city has just begun in May 2023 and brought to light an area of bread ovens (tandyrs/tannῡr) that were built from re-used storage vessels (right).

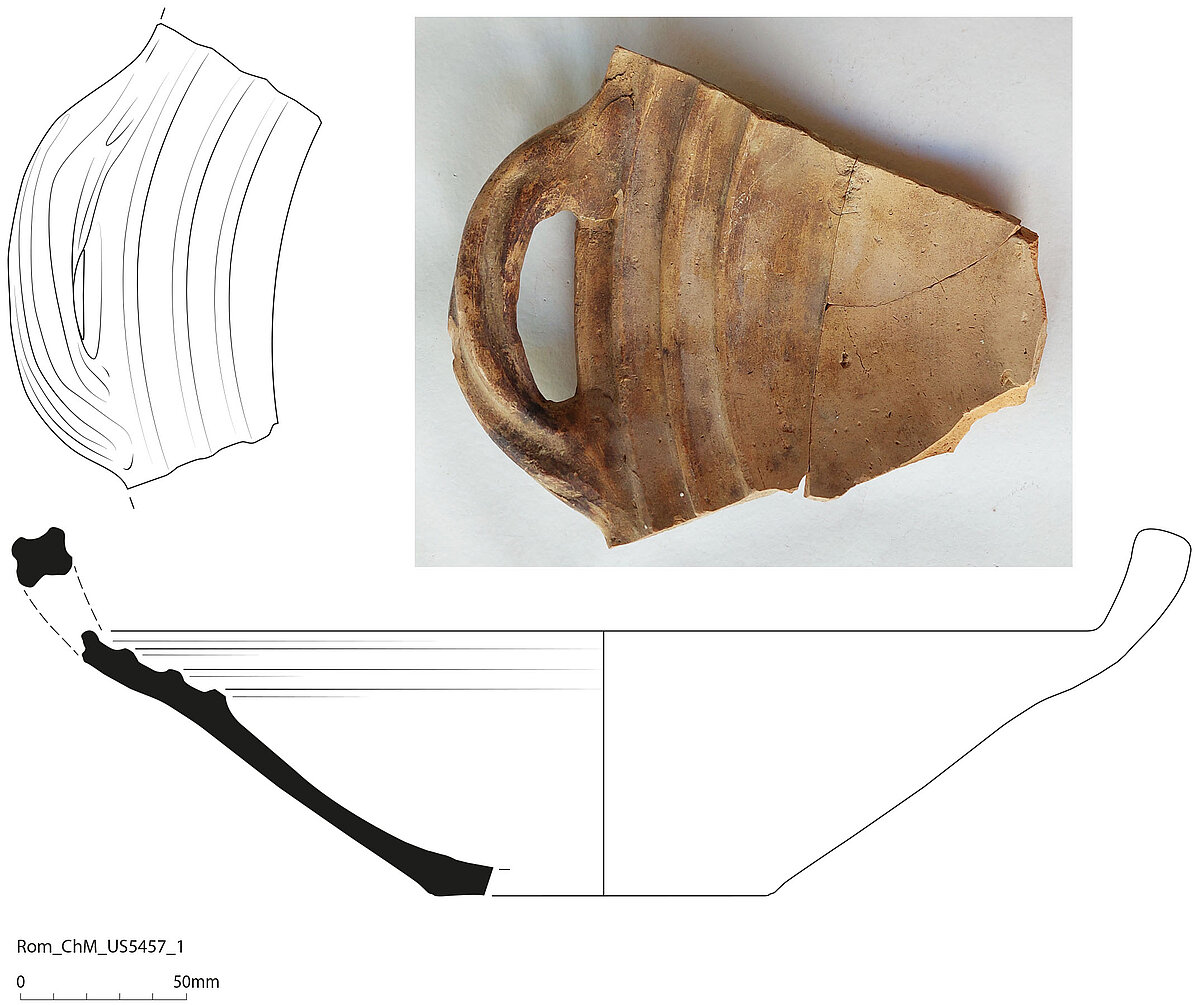

The material found in Ramitan M allowed us to reconstruct some vessel profiles that are usually regarded as rare in Sogdia [Fig. 5]. These are different versions of a large handled bowl, a distinctive shape diagnostic for Bactria and Margiana in the late/post-Kushan and early Sasanian periods respectively (3rd to 4th centuries CE). The specimens from Ramitan are in their design particularly close to bowls from the middle Amu Darya region (Pilipko 1985, pl. 11: 41, 43; pl. 40: 10). In the Bukhara oasis, this vessel type has so far only been documented for Paykend (Semenov and Mirzaahmedov 2007, 96, fig. 44). Some of the closed forms found together with the handled bowls in Ramitan M also show parallels to the Paykend assemblage. The occurrence of the handled bowls specifically prompts us to take a fresh look at Bukhara’s intercultural communication with its neighbouring regions on the one hand and consumption patterns within the oasis on the other. Are these specimens really confined to particular sites or contexts, or is the paucity of evidence due to archaeological chance or sampling bias? We will carefully examine contemporary assemblages from other MAFOUB sites and previous excavations in the oasis to see, how representative the Ramitan assemblage is in the regional context and how it can be interpreted. Samples of the bowls have also been submitted to Dr. Carmen Ting for petrographic analyses to see, if they correspond to the local geology.

Ramitan N yielded material that belongs to phases later than the aforementioned occupation levels of Ramitan M. The re-use of large storage vessels cut in half and turned upside down as ovens illustrates just one aspect in the rich afterlife of these versatile jars (above, left). At the moment, it is difficult to understand, whether this form of use ran chronologically parallel to their function as storage containers, i.e., only concerned broken or damaged jars, or whether it post-dates the use-life of this particular vessel shape for storage. The seal imprint (above, right) found on the shoulder of one of those large storage vessels is of great interest in this regard, and could refer to some kind of administrative activities, storage practices, ownership, or production. The stamp is elliptic in shape and quite deeply imprinted into the vessel shoulder. Unfortunately, the motive is very abraded and difficult to read. Two ovoidal shapes and a wavy line are what is left of the original design. Further studies are needed to identify the motif and contextualise it within the current repertoire of Central Asian sealings. Such seal imprints on jars are relatively uncommon among the archaeological finds due to their rarity in the pottery production as well as the various state of fragmentation of these vessels and subsequently low discovery rate. Large vessels with one or more seal imprints could be found in storerooms or buildings devoted to administrative activities connected to a central authority (such as the collection and redistribution of goods) as in the case of the royal fortress of Old Nisa in Turkmenistan.

Our objectives for the next season are to complete the processing of the material from the two excavations (Ramitan M and N) in order to complete our impression on the potential significance of Ramitan as a city and exchange hub in the oasis during the late antique and late pre-Islamic periods.

References

Pilipko, V. N. 1985. Poseleniya Severo-Zapadnoi Bektrii. Ashkhabad: Ylym.

Puschnigg, Gabriele, and Jacopo Bruno. [2024]. ‘Pottery’. In The Oasis of Bukhara, Volume 3: Material Culture, Socio-Territorial Features, Archaeozoology and Archaeometry, edited by Rocco Rante. Arts and Archaeology of the Islamic World. Leiden; Boston: Brill. In press.

Rante, Rocco, and Jamal Mirzaakhmedov. 2019. The Oasis of Bukhara. Volume 1: Population, Depopulation and Settlement Evolution. Arts and Archaeology of the Islamic World, 12. Leiden; Boston: Brill.

Rante, Rocco, Florian Schwarz, and Luigi Tronca. 2022. The Oasis of Bukhara. Volume 2: An Archaeological, Sociological and Historical Study. Arts and Archaeology of the Islamic World, 17. Leiden; Boston: Brill.

Schwarz, Florian. 2022. ‘Land behind Bukhara. Materials for a Landscape History of the Bukhara Oasis in the Long First Millennium.’ In Rante, Schwarz, and Tronca, 2022: 60–144.

Semenov, G. L., and Dzh. K. Mirzaakhmedov. 2007. ‘Materialy Bukharskoj Arkheologicheskoj Ekspeditsii’. Arkheologicheskie Ekspeditsii Gosudarstvennogo Ermitazha. Sankt-Peterburg: Gosudarstvennyj Ermitazh.