One of the most important discoveries of historical linguistics is the insight that sound change is regular and exceptionless, in the sense that it affects all instances of a particular sound in a particular language. This insight has made it possible to explore interrelatedness among languages and language families (a language family is a group of languages that share a common ancestor or “proto-language”) and discover countless “sound laws”, which initiated the systematic study of language change in general and sound change in particular.

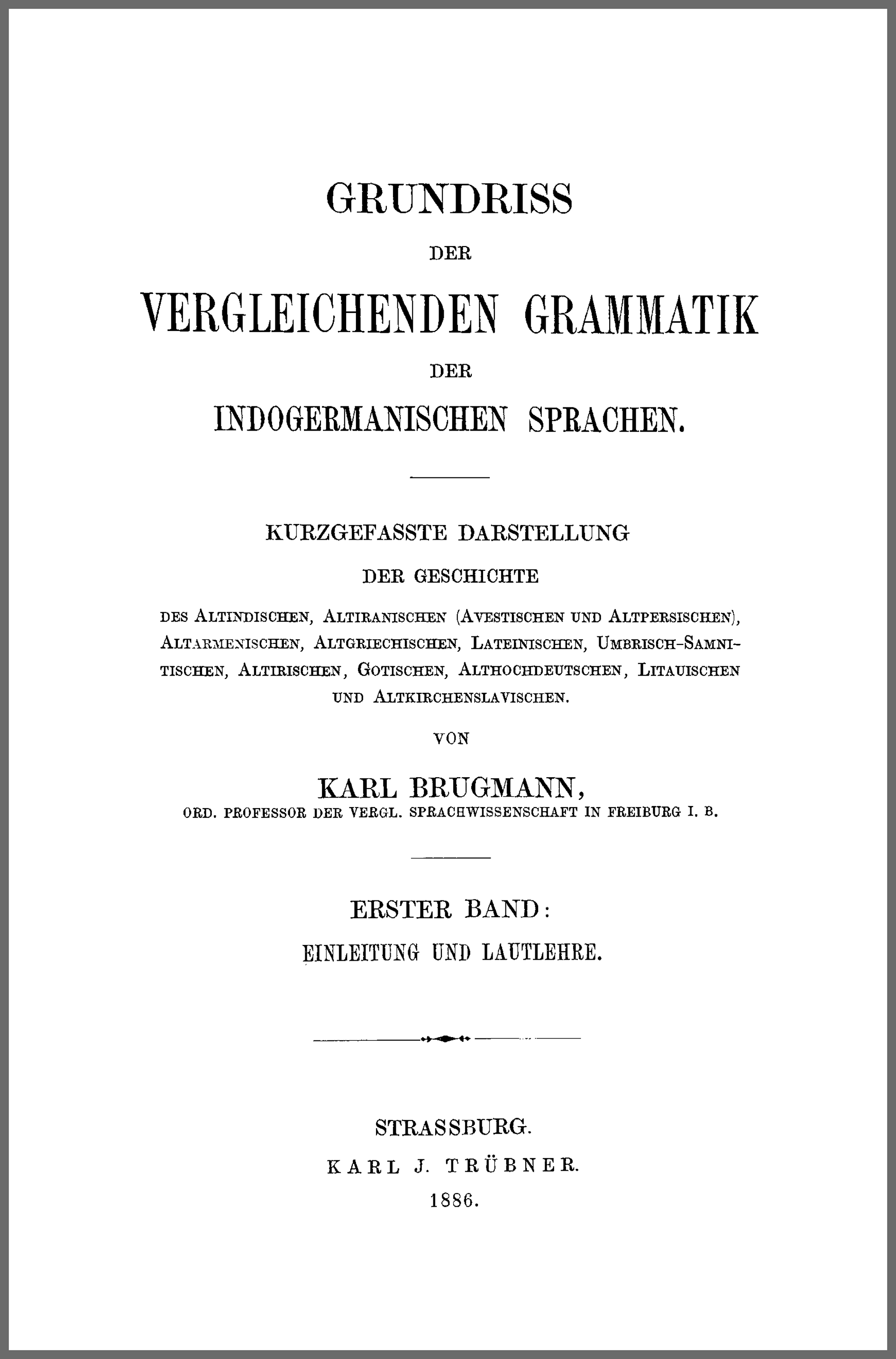

One such law is called “Brugmann’s Law”, after Karl Brugmann (1849 - 1919), who discovered the generalization behind it and published it in 1879, and then a little later in the monumental volumes Grundriss der vergleichenden Grammatik der indogermanischen Sprachen (“Outline of the comparative grammar of the Indo-European languages”, 1886-1893) [Fig. 2]. Brugmann was part of a group of scholars called the Neogrammarians – Junggrammatiker (“young grammarians”) in German – originally a derogatory term used by their contemporaries to make fun of their methodological rigor. The Neogrammarians argued that sound changes actually deserved to be called “laws” because they are regular and exceptionless precisely because a specific condition on their application could be defined, and this condition referred purely to other sounds (and not, for example, to grammatical category or meaning).

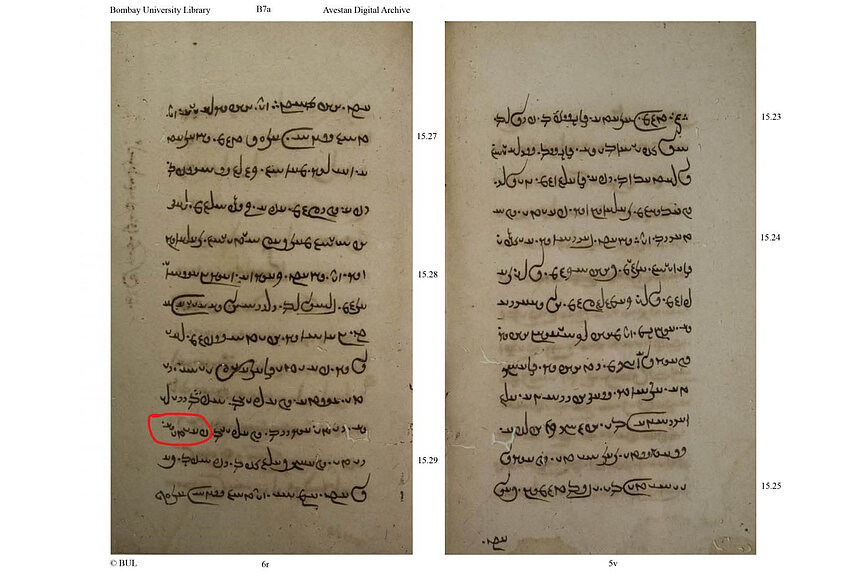

Brugmann’s Law concerns the development of certain vowels in the Indo-Iranian language family [Fig. 3], a large group of languages spoken throughout Central and South Asia (Hindi and Urdu in India and Pakistan, Farsi in Iran and neighbouring countries, and Pashto in Afghanistan and Pakistan being the largest modern examples in terms of numbers of speakers) which is historically related to Greek and the Romance, Slavic, and Germanic languages (among others), which all go back to a reconstructed ancestor language called “Proto-Indo-European” (PIE). PIE was never put into writing, but we can reconstruct what it sounded like based on the evidence of its descendants – attested languages such as Avestan, Sanskrit, Ancient Greek, Hittite and Latin – through regular sound correspondences in related words of these languages. This “comparative method” is at the very core of language reconstruction and the identification of language families.

The ancestor of the Indo-Iranian languages, Proto-Indo-Iranian (PIIr.), underwent specific sound changes that set it apart from the other Indo-European languages. A particularly noticeable one concerns its vowel system: While PIE had five short vowels, *a, *e, *o, *i, *u (the asterisk ‘*’ indicates that a sound or word is reconstructed rather than directly attested in a text) and five long vowels, usually written *ā, *ē, *ō, *ī, *ū, PIIr. reduced its vowels to short *a, *i, *u and long *ā, *ī, *ū. In other words, the vowels *a, *e, and *o all turned into PIIr. *a, while *ā, *ē, and *ō turned into PIIr. *ā in a so-called “vowel merger”.

We can see this mostly clearly by comparing words from Vedic Sanskrit (the oldest attested language of the Indic branch, ca. 1400-1100 BCE), Old Persian (West Iranian, ca. 800-300 BCE) or Avestan (East Iranian, ca. 1200-800 BCE) with their Ancient Greek (ca. 800-300 BCE) equivalents. Ancient Greek was “conservative” concerning its vowel system and kept short e, a, and o and long ē, ā and ō distinct. As can be seen in the following table, Avestan, Old Persian, and Vedic have a’s where Greek has a’s, e’s, and o’s.

Avestan | Old Persian | Vedic | Greek | Meaning |

| abaram | ábharam | épheron | ‘I carried’ |

dadarəsa |

| dadárśa | dédorka | ‘I have seen’ |

bāzuš |

| bāhúḥ | pḗkhus | ‘arm’ |

The Proto-Indo-Iranian vowel merger had far-reaching consequences for Indo-Iranian grammar. In PIE, the differences between vowels, for example between o and e, encoded grammatical information similar to alternations like sing – sang or drive – drove in English, in which the vowel change encodes the difference between present and past tense. PIE used such alternations (called ‘ablaut’), especially between e and o, to encode the distinction between present and perfect, between nominative and genitive, and many others. When Indo-Iranian merged its vowels, these distinctions were no longer possible. This wasn’t a problem for the speakers of those languages – different strategies for marking these grammatical distinctions immediately developed. However, it makes it difficult for historical linguists to find traces of e’s and o’s in Indo-Iranian and hence to determine how particular grammatical categories developed in these languages.

This is where Brugmann’s Law comes in: Brugmann noticed that PIE *o didn’t always turn into Indo-Iranian a as in the table above. When it was followed by only one consonant plus a vowel, or by nothing at all (at the end of a word), PIE *o actually turned into long ā (rather than short a). However, when it was followed by more than one consonant, or by a single consonant at the end of a word, it became a. You can see this by comparing the o’s in the Greek forms in the table below and above to their Indo-Iranian equivalents. In the table above, Greek o corresponds to Indo-Iranian a, while in the table below, Greek o corresponds to Indo-Iranian ā.

Avestan | Old Persian | Vedic | Greek | Meaning |

barāmahi |

| bhárāmasi | phéromen | ‘we carry’ |

dāuru |

| dā́ru | dóru | ‘wood’ |

| asmānam | áśmānam | ákmona | ‘rock’ (acc.sg.) |

Thus, Brugmann’s Law is a generalization about the development of *o in different types of syllables – “open” (when only one consonant or a word boundary follows) vs. “closed” syllables (when more than one consonant or a single consonant at the end of the word follows). Since only *o underwent this change, this makes it possible to distinguish the reflexes of *o from those of *e and *a in “Brugmann’s Law contexts”.

But some puzzles remain: In some words in which we expect Brugmann’s Law to apply in Indo-Iranian and hence to see a long ā, we actually get a, for example in the reflexes of the PIE word for ‘master’, *pótis, which based on the evidence of Greek and Latin must have had *o followed by a single consonant in the nominative and accusative, as shown in the following table. Since the *o was in an open syllable, it should have become *ā in Proto-Indo-Iranian by Brugmann’s Law, and the expected PIIr. Forms and their Vedic and Avestan outcomes are also illustrated in the table (marked with ‘*’ to show that they are not attested). The last two columns give the actually attested Vedic and Avestan forms, which have an unexpected short a and are thus apparent exceptions to Brugmann’s Law.

| Ancient Greek | Latin | PIE | PIIr. (expected) | Vedic (expected) | Avestan (expected) | Actual Vedic form | Actual Avestan form |

Nom. | pósis | potis‘able’ | *pótis | *pā́tis | pā́tiḥ | pāitiš | pátiḥ | paitiš |

Acc. | pósin |

| *pótim | *pā́tim | pā́tim | pāitim | pátim | paitim |

Different explanations for such exceptions have been proposed: for example, maybe there was no *o in the Indo-Iranian reflex but an *e (but there’s no evidence for *e in the other Indo-European languages), or maybe sound change is not “blind” to grammatical information and meaning, after all.

In my article “Sound change and analogy, again: Brugmann’s Law and the hunt for o-grades in Indo-Iranian”, I argue against such approaches and for the Neogrammarian, strictly “blind” application of sound laws like Brugmann’s Law. In the concrete case of the word for ‘master’, for example, the genitive and dative had a slightly different shape than the nominative and accusative: The genitive is reconstructed as *pótjos (j stands for the initial sound in Engl. yes) and the dative as *pótjej, and we see the reflexes of these forms in Indo-Iranian, e.g., in the Vedic dative pátye and the Old Avestan dative paiθiiaē- (PIIr. *pátjaj), as in the following table.

| PIE | PIIr. (expected) | Vedic (attested) | Avestan (attested) |

Nom. | *pótis | *pā́tis | pátiḥ | paitiš |

Acc. | *pótim | *pā́tim | pátim | paitim |

Gen. | *pótjos | *pátjas | páty(ur) |

|

Dat. | *pótjej | *pátjaj | pátye | paiθiiaē- |

Note that the *o was not in an open syllable in the genitive and dative (and in some other forms as well) because *j is consistently treated as a consonant in PIE and in Indo-Iranian (it’s written y in Vedic and ii in Avestan, but these refer to the same sound). Thus, in these forms, the *o is followed by two consonants and therefore not in the right “environment” for Brugmann’s Law. So while it seems as if the law is sensitive to grammatical information (nominative/accusative vs. genitive/dative), it is actually following Brugmann’s original generalization (one vs. more than one consonant). The only additional assumption we need is that the expected shape of the nominative and accusative, PIIr. *pā́t(i)-, was eventually given up by the speakers of Proto-Indo-Iranian, who began to use the non-Brugmann variant *pat(j)- also in the nominative and accusative (this process, called ‘analogy’, is very common in language change).

In fact, as I show in my article, we can often find traces of the older Brugmann variant for many of the examples that have been argued to be exceptions to the law. So sound change is regular – but its effects are often obscured by subsequent changes to the word forms in question. The strictly scientific approach to language change of the Neogrammarians makes it possible to unravel these changes and even find traces of long-lost vowels in languages that haven’t been spoken for thousands of years.