September 10, 2024 | Bill Weis | HI Research Blog

The 9-10th-century fracturing of the Carolingian empire into the polities which would eventually become France and Germany witnessed a concomitant breakdown in the historiographical consensus built up over the previous centuries by the Carolingian dynasty. This ushered in a new era in historical writing, defined by a wider variety of perspectives and witnesses attempting to explain not just why the Carolingian empire fell but, moreover, to understand and legitimize what came to replace, or better to renew it. This context is essential to understanding 11th-century historiography, written at the tail end of this period of reshuffling, as the new dynasties and political communities emerged: indeed, moments of crisis (none as severe as the Investiture Controversy) often shined a light on existing or emerging fissures that arose as various people and institutions were forced to pick one of two sides, spearheaded by either the Salian emperor Henry IV (r. 1054-1105) or the reformist pope Gregory VII (r. 1073-85), figures who were both enormously polarizing. My research is focused on the historiography of chronicles during this period, based on the following question: how did contemporary authors embed earlier historiography into the medium of universal chronicles to grapple with these crises, shape or advocate for a new form of political identity, or giving new meaning to these earlier works? Instead of the traditional approach, in which most studies of these works merely mine these chronicles for a ‘blow-by-blow’ reporting on battles and politicking, I want to turn this approach on its head, bringing attention to the often-ignored parts of these works. More specifically, I am taking a comparative approach to a sample of six different world chronicles—Frutolf of Michaelsburg, Hermann of Reichenau, Lampert of Hersfeld and the Annals of Quedlinburg, Corvey, Hildesheim—which I contend are not only representative of their period but, moreover, embody vastly different viewpoints. Often, they also overlap different historiographical modes, mixing annalistic entries with lengthier prose—as we will see momentarily, this is especially clear in Frutolf’s chronicle. As I am only partway through this project, my blogpost today will focus on the research I have already accomplished on the first three of those authors.

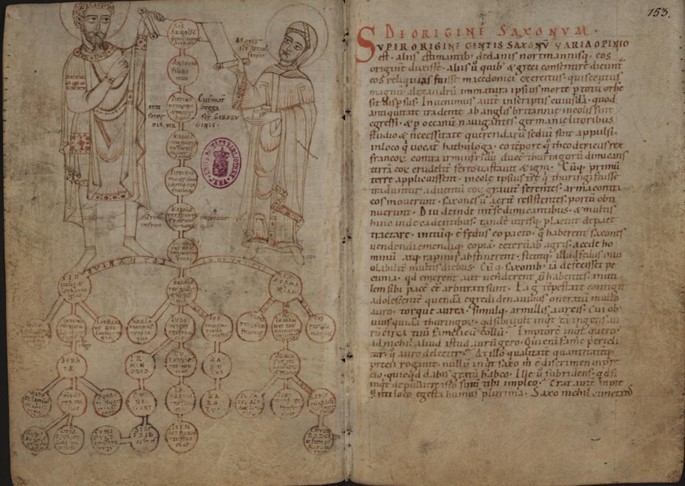

Let’s begin by looking at Frutolf of Michaelsberg’s Chronicle, the work which was ultimately, after a lot of workshopping, the inspiration for this project. Frutolf was a monk at the royal monastery of Bamberg, which had deep ties since its foundation with the Salian monarchy, and he and his host institution supported them staunchly throughout the whole of the Investiture Contest. There are, perhaps, two concepts which are most essential to this project broadly and Frutolf’s work in particular: first is the understanding of medieval chronicles (and world chronicles in particular) as compendia of earlier works, often called—in Ian Wood’s terminology—“chains of chronicles.” Frutolf’s jumping-off point was the 4th-century Eusebius-Jerome chronicle, in which Eusebius attempted to synchronize the dates of various peoples throughout biblical history, each with their own dating systems, up until his own day during the reign of the first Christian emperor, Constantine I (r. 306-37). This gave the work of Eusebius-Jerome and, consequently Frutolf, two emphases—synchronous dating and ethnography. Frutolf, in order to continue this 4th-century chronicle until his own day in the 11th century, stitched together chronicles from across the early Middle Ages (such as the 5th-century Gallic Chronicle of Prosper of Aquitaine or the 9th-century Royal Frankish Annals). However, in updating the work, Frutolf encountered a problem: how was he to explain the decline of the Romans and their empire (the nadir of Eusebius-Jerome’s work) as well as their replacement with several different barbarian peoples? In order to explain this away, Frutolf invoked the concept of translatio imperii, the idea of a persistent concept of empire, a hegemonic entity with an important eschatological role that is transferred between different peoples/polities throughout history. This was not a novel concept, but had a deep history centered on biblical prophecy, chiefly in the Book of Daniel, wherein the 6th-century BC king of Babylon, Nebuchadnezzar II, dreamed about a statue made of four different metals, which the prophet Daniel interpreted as a symbolization of a progression of empires. As a consequence, Frutolf interpolated multiple ethnographic works (such as Jordanes’ legendary 6th-century Origin of the Goths) to explain the origins of these peoples and the role they would ultimately play in salvific history. This process is readily apparent in the picture of Frutolf’s manuscript above, which depicts a Carolingian genealogy followed immediately by a work explaining the origin of their successors, the Saxons. Ultimately, Frutolf’s unique emphasis laid in the creative tension between the eternal concept of empire and the very temporal concept of the rise and fall of various peoples.

Next, let’s turn to Hermann of Reichenau’s chronicon, which offers a sharp contrast with Frutolf’s work. Like Bamberg, Reichenau too was an imperial monastery with deep ties to the ruling Ottonian and Salian dynasties: however, unlike Bamberg, it was swept up in the church reform movement prevalent in south-western Germany as well as the rebellion of Rudolf of Rheinfelden—crowned in 1077 by Pope Gregory VII as a rival to Henry IV for the throne—two events which were intimately linked. Though these movements took place shortly after Hermann’s death, they deeply affected two continuations of his work by his pupils, Berthold and Bernold: it is important to recognize that they would ultimately flip Hermann’s work on its head, turning its initially pro-Salian narrative into papal polemic. The most significant contrast between this work and the previous is that, eschewing the ethnographic focus, Hermann’s chronicle was focused on the concept of empire throughout time, linking it with the East Frankish people, the concept of a “just king,” and the nascent church reform movements. With only one important exception, Hermann did not break the annalistic format; nevertheless, this exception, where Hermann inserted Wipo of Burgundy’s Deeds of Conrad II (r. 1027-39), a commentary from earlier in the same century on the deeds and virtues of the first Salian emperor after the Ottonian dynasty fizzled out, is the key to unlocking the meaning of the whole text. First, it introduced the Salian dynasty and explained why they deserved to rule after the scramble for power following the death of Henry II (r. 1014-24), the final Ottonian monarch. More than this, Wipo’s philosophy of kingship (see Sverre Bagge’s work cited below), which was itself deeply influenced by the 6th-century author Isidore of Seville, would exercise enormous influence of how Hermann conceived of proper rulership: for Hermann this work would prove to be the measuring stick against which all rulers should be measured and, consequently, explaining why the Salians continued to be worthy to rule even up to his own day. However, due to his anti-Henrician continuators Berthold and Bernold, this would ultimately prove to be a double-edged sword: in their independent continuations it was Henry IV who was measured against this ideal model and routinely found lacking. In short, then, Hermann’s work emphasized virtue and proper kingship as the necessary precepts for legitimacy, engaging heavily with the genre of speculum principis, mirrors for princes.

Finally, I’ll offer another brief point of comparison by looking at Lampert of Hersfeld’s Annals. Unlike the previous two authors, Lampert was avowedly pro-papal, composing the most detailed (and most polemical) contemporary account of Henry IV’s reign. This is a particularly peculiar fact, given that his home monastery of Hersfeld proved unquestioningly loyal to Henry during the period, which has led historians to hypothesize about the motive behind his provocative history. Was Lampert, having been passed over for promotion as Abbot of Hersfeld, personally angry with Henry? Did he rue the strain put on his monastery when it was forced to quarter Henry’s ravenous army during the Saxon Rebellions at several different points from 1077-88? Or was this evidence of a significant minority faction at Hersfeld which chafed under imperial rule, trying to persuade the rest of the monastery to defect to Rudolf of Rheinfelden’s rebellion? These questions are, of course, necessarily speculative, but are nevertheless intriguing. More than this, Lampert’s work was also an outlier in that it entirely eschewed the ethnographic tropes which were so prevalent in Frutolf’s, as well as Hermann’s deep interest in the genre of the world chronicle: indeed, in Oswald Holder-Egger’s classic edition of the text from 1896, the entire history of the world from creation until 702 occupied only six pages. Instead, Lampert was preeminently concerned with displaying his erudition, paraphrasing from over 40 of the most famous works of Latin literature, with a particular focus on authors like Cicero, Horace, and Ovid from the “Golden Age of Latin literature” (70BC-18AD, roughly contemporary with the demise of the Roman Republic). It was Guido Billanovich who first drew attention to Lampert’s stylistic dependency on Titus Livy, the famous historian of Rome from the 1st century AD. As a result, many have dismissed Lampert as derivative, inaccurate, or melodramatic, but I believe this is unfair: as I hope to lay out in my forthcoming chapter, Lampert (and the other authors sampled in the dissertation) were extremely well educated, often within the same social networks and with access to the same libraries. In particular, the cathedral school of Bamberg was especially famous for producing important Salian advisors and churchmen: these references and paraphrases, which now appear arcane in our modern world, would not have been lost on his audience and would have conjured up powerful historical parallels in the minds of his readers, who would likely have been other well-educated churchmen and, possibly, his fellow brothers at Hersfeld. Take for example Lampert’s entry describing Henry as “hated by all men and suspected by all men” (trans. Ian Robinson, The annals of Lampert of Hersfeld, 2015), a paraphrase of Livy’s famous account of the 2nd century BC ruler Perseus of Macedon: in Livy’s retelling, Perseus was a man so evil, so infamous for murdering and pillaging his own citizens, that he deserved to lose his kingdom to the impending Roman invasion. Lampert thereby establishing a strong typological link between these two rulers, one which would not be lost on his audience, that Henry too, like Perseus, deserved to lose his kingdom to the more virtuous Rudolf of Rheinfelden.

I'll begin to wrap up by summarizing our various authors so far: Frutolf saw history as defined by the rise of the church and an empire, as well as the intermingling of various gentes within this framework; Hermann, by contrast, emphasized the institutional empire throughout time and the role of virtue in just kingship; finally, Lampert’s chronicle took yet a third angle, drawing from classical ideas of government and using allusion to criticize Henry IV. More than this, this study speaks to existence of a wide range of ideas during this period, a spectrum which was in part responsible for the Investiture Conflict, about how to constitute a community both at a regional/institutional level as well as more broadly, on the level of the whole empire. And yet none of these authors questioned the concept of the empire itself, because of its all-important eschatological function, but instead squabbled over how to interpret the empire and who should rule it and how. Ultimately, these works give voice to the variety of ways that imperial authority was understood, and ultimately upheld or questioned, at various institutions or regions within the empire.